Liberalisation is women`s liberaliser

Is a point well made, and bravely too since it runs contrary to the prevailing doctrine of political correctness. “Women’s issues” are now very much part of the professed agenda for parties across the political spectrum. This is, no doubt, a good thing. The problem is that the issue has acquired a moral absolutism that is unlikely to deliver effective results. Too often, politicians make attention-grabbing efforts to promote the cause of women. They end up achieving a gender differentiation that does little to help the cause.

The (fortunately) long-delayed Bill to reserve 33 per cent of the seats in the lower House of Parliament is a case in point. The political circus that has thrust Pratibha Patil as presidential candidate—perhaps the most cynical exploitation of the women’s cause for political ends—is another.

I am not sure of their destination, nor the reason that they undertook what I am sure was a long journey to Delhi. I do know that they were very enthusiastic. One often sees such women and men peasants seeking justice in the seat of government. I wanted to write, "Til we out number them," but wonder if women here.

I am not sure of their destination, nor the reason that they undertook what I am sure was a long journey to Delhi. I do know that they were very enthusiastic. One often sees such women and men peasants seeking justice in the seat of government. I wanted to write, "Til we out number them," but wonder if women here.

Now, not to be outdone, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is considering the idea of reserving a third of party membership for women. Even if you disagree with its politics, the BJP should really know better. The senior women in its ranks all owe their position to their own abilities. Reserving positions in the party for women amounts to an insult. Parliament and political parties are—in theory at any rate—supposed to administer the welfare of the people who vote for them. It is not obvious that women are uniquely qualified than men to achieve this. Surely ability should count for more than gender in such circumstances? There is also no established connection between women in power and women’s empowerment. Had that been the case, India should have become a haven of gender equality during Indira Gandhi’s 15-year rule (in two stints) as prime minister. Marking out women for special treatment in public institutions in which merit is the overriding criterion makes a mockery of the movement for gender equality. It singles out women as a group requiring special treatment and reinforces prejudices about the “the weaker sex”. In policy terms, positive discrimination is more likely to work if it is applied to meet practical needs. Reserving or subsidising public education for the deprived girl-child, for instance, is a good way to start bridging the gender gap. But since it is a less visible way of co-opting the empowerment agenda than reserving seats in Parliament, it is unlikely to find many takers. This does not mean that women’s issue should be ignored. Despite being the cynosure of global interest, India has an appalling track record in terms of gender equality. The laws against domestic violence, dowry and sex-determination tests are enlightened pieces of legislation in that respect, even if their implementation requires some bolstering. So what’s to be done? It may sound strange and tangential, but the answer partially lies in economic liberalisation. The demands of economic growth and competition, where talent is a coveted but gender-neutral asset, can be an automatic guarantor of gender equality.

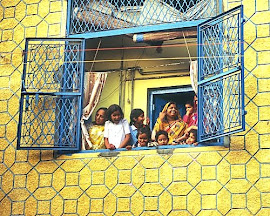

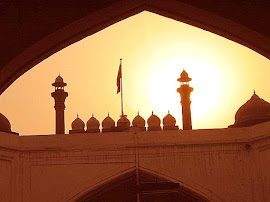

This is part of images from my effort to work my way around Delhi on the Ring Road. Raj Ghat is at the center of a series of parks and memorials that line the Ring Road near "Old Delhi." While exploring around this area, I encountered these very colorful women.

This is part of images from my effort to work my way around Delhi on the Ring Road. Raj Ghat is at the center of a series of parks and memorials that line the Ring Road near "Old Delhi." While exploring around this area, I encountered these very colorful women. The growing participation of women in the workforce is already starkly visible in a host of industries that have flourished after the licence-raj was dismantled—outsourcing units, telecom, pharma, insurance and banking. Few of the women in these businesses are not fierce feminists—indeed, a BusinessWeek article once showed that they often come from conservative homes. Yet, the empowerment that flows from an earned income is both real and enduring and, over the long term, has a multiplier impact on women’s well-being. History has demonstrated that women’s rights have always been won on the altar of necessity. In Britain, women won the right to vote after their sterling work in World War I as support staff, manning the factories and driving trucks and ambulances. In the US, 48 states made it illegal for married women to work. That changed after World War II, when the factories that produced armaments started producing consumer goods—and needed people to work them—to meet the post-war American boom. To be sure, the transformation is a long and hard one. A study by Accenture titled “Breaking the Glass Ceiling” shows that women executives still find it relatively tough going even in evolved economies such as Australia, Germany, the UK, the Philippines and Switzerland. Accenture calculated a Glass Ceiling Index on a scale of 1 to 6 (6 being the thickest). Ranked on three dimensions of individual, company and country, the Index ranged between 2.6 and 3.8 for the first, 3 and 4.8 for the second and 2.8 to 5 for the third. Significantly, the figures above demonstrate—and women executives surveyed corroborated—that companies were doing a better job than society to promote women’s individual needs. Gender equality can never be achieved overnight. But more liberalisation, which unleashes the capabilities of India’s corporate sector, will probably bridge the gender gap faster than forced policy prescriptions.

.jpg)

.jpg)

0 comments:

Post a Comment